As I enter retirement age, I find myself doing 99% of my writing electronically. Lately, I’ve been noticing a rise in romantic nostalgia among writers who idealize the trusty tools of the past: quills, typewriters, fountain pens. While these implements may be charming, I think we’re missing the forest for the trees.

As a psychotherapist who has worked with children grappling with early learning challenges, I've observed our natural tendency to look back with heartfelt and comforting nostalgia to the good old days, often glorifying vintage technologies like daguerreotype photography, horse-drawn buggies, or steam engines. We fondly recall their reliable utility and at the same time conveniently forget why they were replaced.

Sigh.

We see this in the alluring steampunk ethos and frequently in discussions about writing, where the tactile click click click of a mechanical typewriter or the deliberate scrape and tap of a graphite pencil across textured paper is longed for like an idyllic childhood and celebrated as far more authentic than the lightning-fast instant gratification of an electronic screen.

While these older writing tools possess charm and perhaps instilled helpful disciplines, they are only the “trees” in a much larger “forest.” The actual forest, the overarching value, lies in clear, coherent thinking, expression, and the power of observation.

My critique isn't aimed at those who thoughtfully choose analog tools as part of their deliberate creative process. Writers like Ocean Vuong, who draft by hand as an intentional method of connecting with language and slowing down thought, are making conscious choices that serve their unique creative needs. What I'm questioning is the romanticization that elevates these methods as inherently superior or more “authentic” for everyone.

As a psychotherapist, I've spent decades observing how people use language—both verbal and nonverbal—to express their innermost thoughts and navigate their worlds. In countless sessions, I've witnessed how expression itself, regardless of form, facilitates healing and connection.

A client might find catharsis through spoken words, written journals, artistic creation, or simple movements, but the therapeutic value comes from the expression, and the trust built, not the method, the techniques. This work has deepened my understanding that language—our ability to formulate and communicate meaning—is the true forest we need to be tending, while the specific tools of expression are merely the trees within it.

Proponents of typewriters highlight their limitations as virtues: the care and maintenance, the cost of paper and ribbon, the permanence of each keystroke, and the labor of correction are said to foster mindfulness. I remember draining bottles of Whiteout, their sides streaked with dried drips, tediously brushing over error after error after error. That’s not what improved my writing.

These built-in speed bumps did force a deeper engagement with language. There's truth to that. Slowing down is essential in the digital age. But there's also a point of diminishing returns where romanticizing becomes excessive. (No disrespect, but if I hear another writer sing about the virtues of pencils or typewriters, prepare for projectile vomiting.)

Similarly, discussions about teaching cursive handwriting often emphasize neurological benefits and unique cognitive pathways. These “virtues” suggest superior learning and deeper connection to language. Early learning shouldn't be rushed, and there's value there. Such are the perils of public education.

While idealizing a tool is heartwarming, it neglects something fundamental: quality writing isn't about the physical act of transcription, but the internal process of formulating and communicating ideas from observations. Telling stories. The pencil, pen, keyboard, typewriter – these are mere conduits. When we obsess over the conduit, we diminish the significance of the message itself.

Of course, a beautifully written page can still contain destructive ideas. History offers chilling proof. The antisemitic Mein Kampf stands as a stark example of how a hate-filled message can be utterly reprehensible, regardless of whether it was conceived with a pencil, dictated, or typed.

More critically, this sentimental focus on particular tools isn't just misguided; it creates an ableist barrier to inclusion. For someone with dysgraphia, handwriting can be agonizing, consuming cognitive energy and leaving little room for content.

We make jokes about “doctor's handwriting” precisely because brilliant physicians often produce barely legible prescriptions. We don't judge physicians by penmanship but by diagnostic accuracy—and writing should be no different.

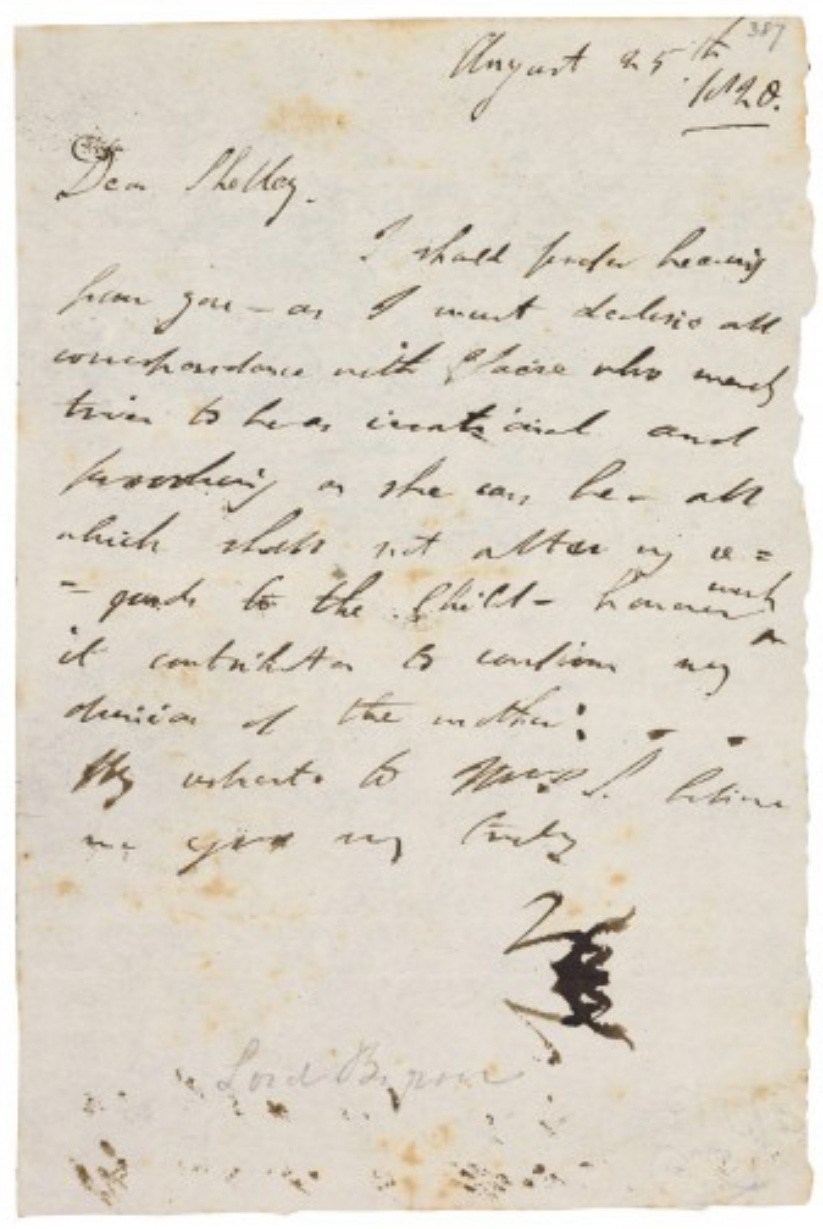

Here’s an example of Lord Byron’s handwritten letter to Shelly (see photo below):

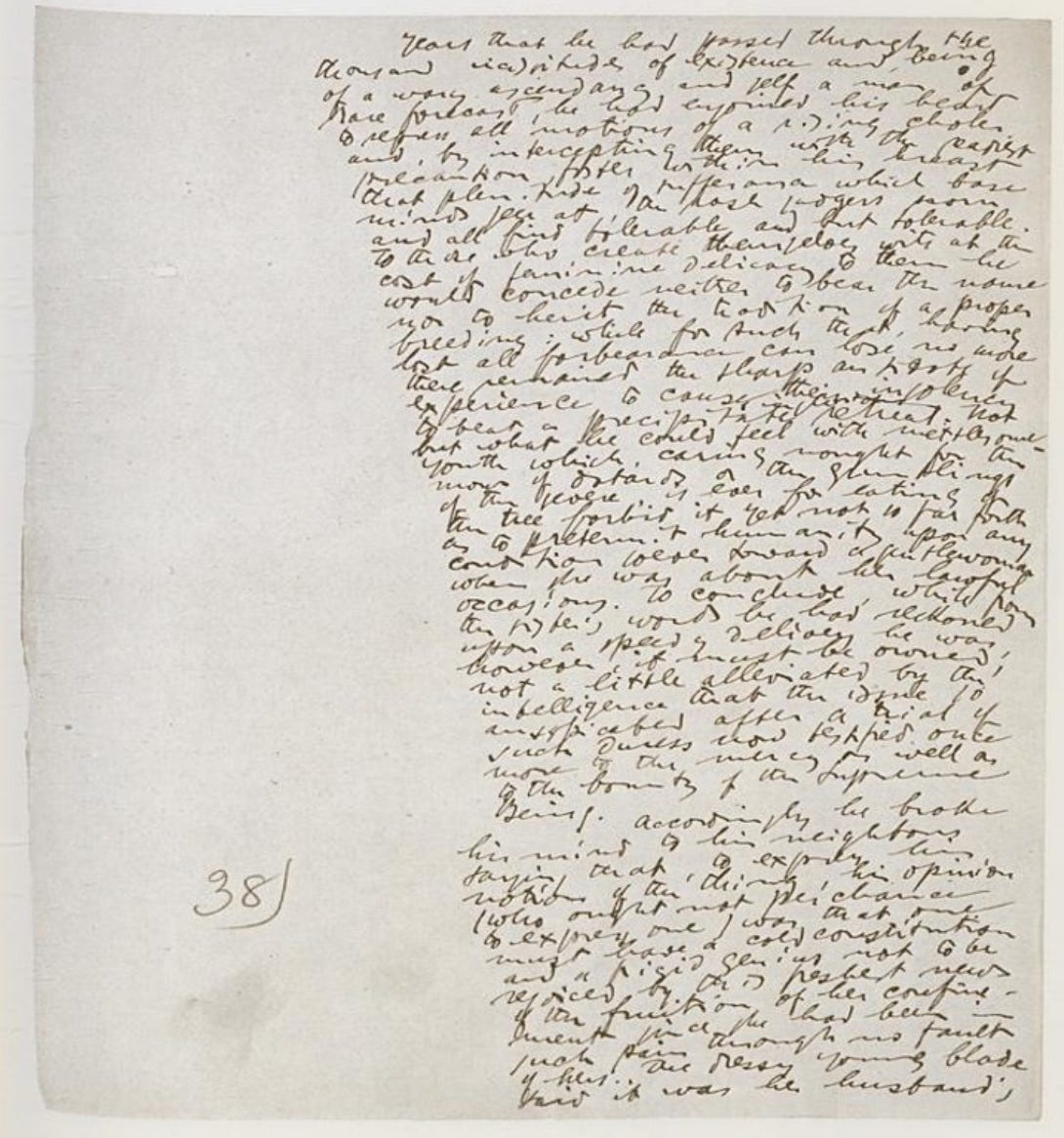

And here’s another example from James Joyce (see photo below):

Physical limitations —from arthritis to visual impairments to the loss of hands— can make traditional writing implements impossible to use.

I think of Stephen Hawking, who “wrote” groundbreaking work while unable to move or speak due to ALS. Despite his limitations, he published influential scientific papers and books like A Brief History of Time. Other historical examples of adaptive writing include Milton dictating Paradise Lost after losing his sight, and much later, Agatha Christie using audio recording technology, a Dictaphone, for her works.

Mark Twain experimented with Edison's phonograph in the 1890s, dictating portions of his writing to wax cylinders later transcribed by an assistant. Though he quipped that the phonograph “hasn't any ideas,” he utilized it to relieve his rheumatic arm.

These historical figures demonstrate a crucial truth: great writing has always transcended the specific tools used to capture it. Throughout history, writers have adapted to physical limitations and embraced available technologies.

This tradition continues with modern digital technologies —voice-to-text software, specialized input devices, screen readers – are not just conveniences; they are enablers of expression. They democratize writing, unlocking the ability to compose and share thoughts (even destructive ones) for millions who would otherwise be marginalized and silenced.

When someone dictates a complex story or crafts a compelling argument using only their voice, are they not “writing”? Absolutely. The act of composition —the organization of ideas, the choice of vocabulary, the shaping of sentences— occurs in a particular mind or soul, a unique consciousness, with technology serving as a transparent, assistive bridge to the written word. An instrument.

To insist that “authentic” writing must conform to specific historical methods misses the forest for the trees. It prioritizes antiquated mechanics over purpose. While disciplines might have been fostered by older tools, those disciplines are achievable regardless of instrument. An experienced musician can make music from a tongue depressor; a beginner could never make a Stradivarius sing. A mindful writer can be disciplined with an iPad, and a careless one can produce rushed prose on a clunky typewriter.

This focus on purpose extends to newer tools like artificial intelligence. AI represents the next evolution in writing implements. Like the typewriter in its day, AI is often misunderstood. But its value isn't in replacing thinking, but in expanding engagement with our tools. Used wisely, AI becomes a mirror and collaborator, helping clarify, not replace, ideas. The goal is accessibility and clarity, not dependence.

Our primary focus, both in education and in personal expression, needs to remain anchored to the clarity, coherence, and impact of our ideas. The newer tools that expand this possibility—especially those that give voice to the previously silenced—aren't just conveniences; they're moral imperatives for a better future.

So yes—let’s appreciate the rigorous discipline once demanded by quills and typewriters, and the neural pathways cursive might continue to develop. But let’s not allow nostalgia become exclusion. For every child liberated by a keyboard, for every adult who finds voice through voice recognition, the insistence on tradition isn’t just outdated—it’s cruel and unjust.

The art of writing was never in the medium but in the message—not in how we put words on a page, but in how those words resonate, challenge, and transform us as human beings. This is the forest we need to see, protect, and expand for all who wish to enter.