Fighting for Democracy

A Psychotherapist Stands Up for Democratic Values

As a psychotherapist, my daily work involves helping individuals and families develop self-awareness, authentic connection, and relational health. When I observe the current political environment—particularly proposals like Project 2025 and the movement toward concentrated executive power—I find myself drawing on my professional experience not to diagnose political opponents, but to understand how we as a nation arrive at support for policies that threaten democratic pluralism.

My Method & Intent

I want to be clear about what I’m attempting here. I’m not pathologizing conservative politics or policy disagreements about economics, regulation, or the proper size of government. Those are legitimate areas of democratic debate. Rather, I’m trying to understand the thought patterns that make authoritarian proposals seem reasonable or necessary to good-faith citizens—proposals that would fundamentally restructure democratic institutions, concentrate power in the executive branch, and privilege particular religious perspectives in governance.

My goal is not to dismiss fellow citizens as mentally unwell, but to explore how certain ways of thinking about politics—ways we all can fall into under stress or fear—can lead us away from the demanding work of sustaining democratic pluralism. If we want to persuade rather than dismiss, we must first understand.

Recognizing Patterns That Distort Political Thinking

In therapy, we help people recognize thought patterns that create unnecessary suffering or prevent them from seeing situations clearly. Similar patterns appear in political discourse across the spectrum:

Magnification & Crisis Thinking: When political rhetoric relies heavily on catastrophic language—presenting every election as an existential crisis, every policy disagreement as civilization-ending—it becomes difficult to engage in the patient, incremental work of democratic governance. This isn’t unique to any one movement; we all do it when we’re afraid. We are human. The question is: what happens when crisis rhetoric becomes the default mode of political engagement?

Binary Black & White Thinking: The division of the world into pure “us” versus irredeemable “them” is psychologically simpler than holding complexity. It’s easier to believe our side contains only virtue and the other only vice. But democracy requires us to do the harder thing—to recognize that all political coalitions contain both principled concerns and problematic elements, to see that people we disagree with often have legitimate grievances even when we think their solutions are misguided.

A healthy democracy requires the psychological capacity to sit with nuance and ambiguity, to recognize shared humanity even amidst deep disagreement. When we lose that capacity collectively, we become vulnerable to proposals that promise simple certainty.

The Role of Fear & the Need for Empathy

Fear is perhaps the most powerful force in politics, and understanding this is key to understanding how people come to support authoritarian solutions. When communities feel genuinely threatened—economically displaced, culturally alienated, or unheard by institutions—the appeal of a strong leader who promises to cut through complexity and “fix” everything becomes very real.

Millions of Americans supporting policies I find troubling are responding to real experiences: manufacturing jobs that disappeared, communities struggling with opioid addiction, a sense that cultural changes are happening too rapidly, or religious communities that feel their values are no longer welcome in public life. These aren’t imaginary concerns, even if I believe the proposed solutions would harm democratic institutions.

My counter-vision insists that we must design policies by genuinely understanding and responding to these concerns, not dismissing them:

Economic Security: Rather than scapegoating immigrants (e.g., “Somalis are garbage”) or global trade, we could address the real economic uncertainty through living wages, robust retraining programs, and a tax system that works to disincentivize concentrating wealth at the very top. This acknowledges low-wage anxiety without directing it toward authoritarian nationalism.

Universal Systems: Policies like universal healthcare and affordable education recognize that many Americans feel left behind not because of who’s crossing borders, but because basic stability feels out of reach. When families feel secure, they’re less vulnerable to fear-based politics.

Cultural Listening: We need spaces where Americans with different values can genuinely discuss concerns about community, tradition, and change without one side being dismissed as bigoted and the other as tyrannical.

Naming What Cannot Be Tolerated

Understanding why people support certain leaders is not the same as tolerating what those leaders say and do. We can hold both truths simultaneously: that many voters have legitimate concerns, and that some political rhetoric crosses clear moral lines that cannot be accepted in a democratic society.

When political leaders use white supremacy dog whistles, when they call entire ethnic groups “garbage,” when they traffic in dehumanizing language—this is not just “controversial” or “politically incorrect.” This is rhetoric that has historically preceded violence, that corrodes the possibility of democratic pluralism, that makes it impossible for targeted communities to participate as equal citizens.

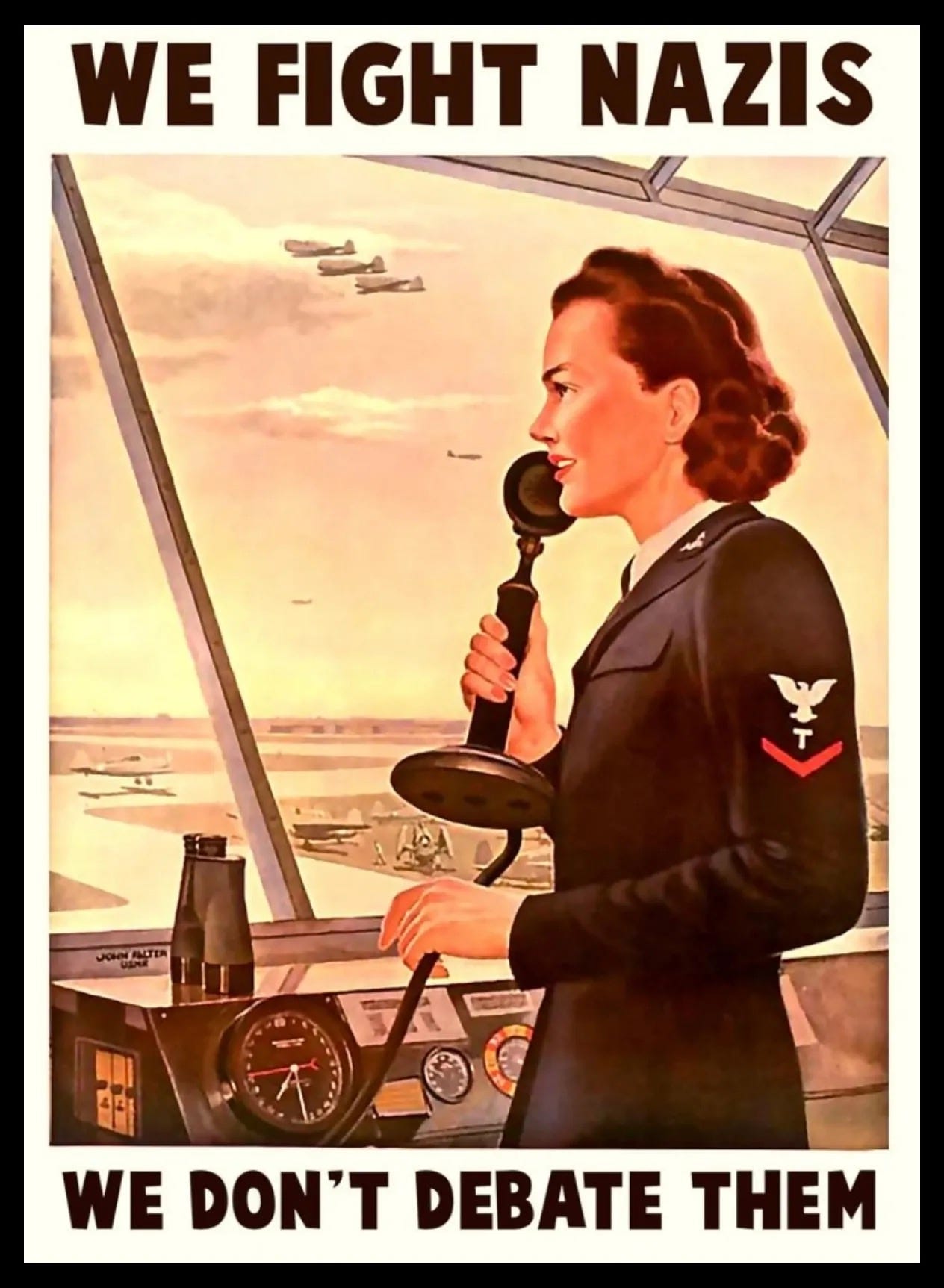

We must name this clearly and oppose it forcefully. Not because we want to “cancel” people or shut down debate, but because democracy itself depends on a baseline commitment: that all people living in the United States are fully human and deserving of dignity. Rhetoric that violates this baseline—whether through overt racism or coded appeals to racial resentment—must be met with clear moral condemnation and organized resistance.

This means:

Calling it out specifically: Don’t soften or euphemize. If it’s a white supremacy dog whistle, say so. If it’s dehumanizing language, name it as such.

Organized opposition: Supporting leaders, organizations, and movements that actively counter this rhetoric and defend targeted communities.

Not letting it become normalized: Refusing to treat deeply harmful rhetoric as just another policy disagreement or acceptable political strategy.

Here’s the distinction I’m making: We don’t legitimize fascist ideology by treating it as just another viewpoint. We oppose it directly. But here’s the harder strategic question: How do we prevent fascist movements from recruiting? How do we keep ordinary citizens—people facing real economic and cultural pressures—from being drawn into authoritarian movements?

That requires understanding why the recruitment works, so we can offer something better. We can and should work to understand why voters facing economic anxiety or cultural displacement become susceptible to this rhetoric. But we don’t have to treat the rhetoric itself as legitimate, and we don’t have to treat leaders who deliberately employ it as operating in good faith.

The work of persuasion is helping voters see that leaders using this rhetoric are exploiting their real concerns rather than addressing them—and that there are alternative leaders and policies that would actually respond to their needs without requiring anyone to dehumanize their neighbors.

We can stand up. We can fight back.

Accountability & the Erosion of Democratic Norms

One pattern I find particularly concerning is the normalization of rejecting accountability—the denial of responsibility, the projection of blame onto institutions, the suggestion that certain leaders should operate above legal constraints. This isn’t about any one person; it’s about what happens when we decide as a nation that our preferred leaders deserve special exemptions from the rules. This clearly is counter to one of our most cherished founding documents, the Declaration of Independence.

Democracy requires something psychologically difficult: the willingness to subject even our own side to scrutiny, to acknowledge when our leaders fail or overstep, to tolerate inconvenient truths. When we lose that capacity, we drift toward authoritarianism regardless of our stated ideology.

A mature democracy must be capable of:

Equal Accountability: Insisting that all officials, regardless of party or popularity, are subject to the same legal standards. When we make exceptions for “our” leaders, we undermine the very framework that protects everyone.

Institutional Independence: Defending the independence of courts, the Justice Department, and the press—not because they’re perfect, but because they’re the mechanisms designed to prevent any one faction from consolidating total control.

Historical Honesty: Being willing to confront difficult truths about our history and present, whether that’s systemic racism, economic inequality, or the ways various political movements have failed to live up to democratic ideals.

Moving Toward Democratic Resilience

The current political moment represents a test of our collective psychological maturity. When we’re afraid, it’s tempting to retreat into certainty, to embrace leaders who promise to eliminate complexity, to divide the world into good people and bad people. These are human impulses, not signs of individual pathology.

But sustaining democracy requires us to resist these impulses. It requires:

Choosing dialogue over demonization

Seeking to understand why people support what they do before dismissing them

Holding complexity even when simplicity feels more satisfying

Building systems that respond to everyone’s legitimate needs, not just our coalition’s priorities

This is demanding work. It’s much easier to believe that people who disagree with us are simply cognitively impaired or morally bankrupt. And certainly, some rhetoric—like calling entire ethnic groups “garbage”—is morally indefensible and must be condemned unequivocally. But the harder question is: why do otherwise decent citizens support leaders who speak this way? Dismissing millions of voters as irredeemable prevents us from understanding what makes such rhetoric politically viable—and therefore prevents us from building the alternative that could actually prevail.

If we want to prevent the erosion of democratic institutions—if we want to write a counter-narrative to authoritarianism that actually persuades rather than just preaches—we must start by treating political opponents as fellow citizens with legitimate concerns, even when we believe their proposed solutions would be disastrous.

Only through this kind of sustained, empathetic engagement—combined with unflinching opposition to dehumanizing rhetoric and authoritarian proposals—can we build the broad coalition necessary to defend democratic pluralism and move toward a more equitable, resilient American future. We can stand up. We can fight back. And together, we can create a better tomorrow.

Letters from a Psychotherapist is a reader-supported, ad-free publication, but there are expenses. By subscribing, you directly help keep this content accessible to everyone, regardless of their financial situation, while also supporting my work. Thank you for reading and being part of this community.