(Adapted from my previous memoir, My Mother’s Ghosts.)

When Dad died in the summer of 2001, there was no money to inherit, no estate for him to bequeath. He had been living on Social Security for 20 years. Though he lived into the new millennium, he was a product of the previous century. I did my best to deliver a heartfelt eulogy for him at the funeral home, as I had done for my mother five years earlier. I guess sometimes you get thrown into this writing thing. I curated a silent slide show of his old construction photographs endlessly looping from a laptop in a parlor adjacent to his opened casket.

I made sure to slip in a yellow legal pad and a sharpened number two pencil under his lifeless right hand—his writing hand. My younger brother Russell gave up a silver bracelet engraved with his name. Dad’s elderly sister Alberta offered a modest cross and gold chain. Someone nestled in a golf ball. An attorney in the extended family offered his business card —in case Dad needed a lawyer where he was going.

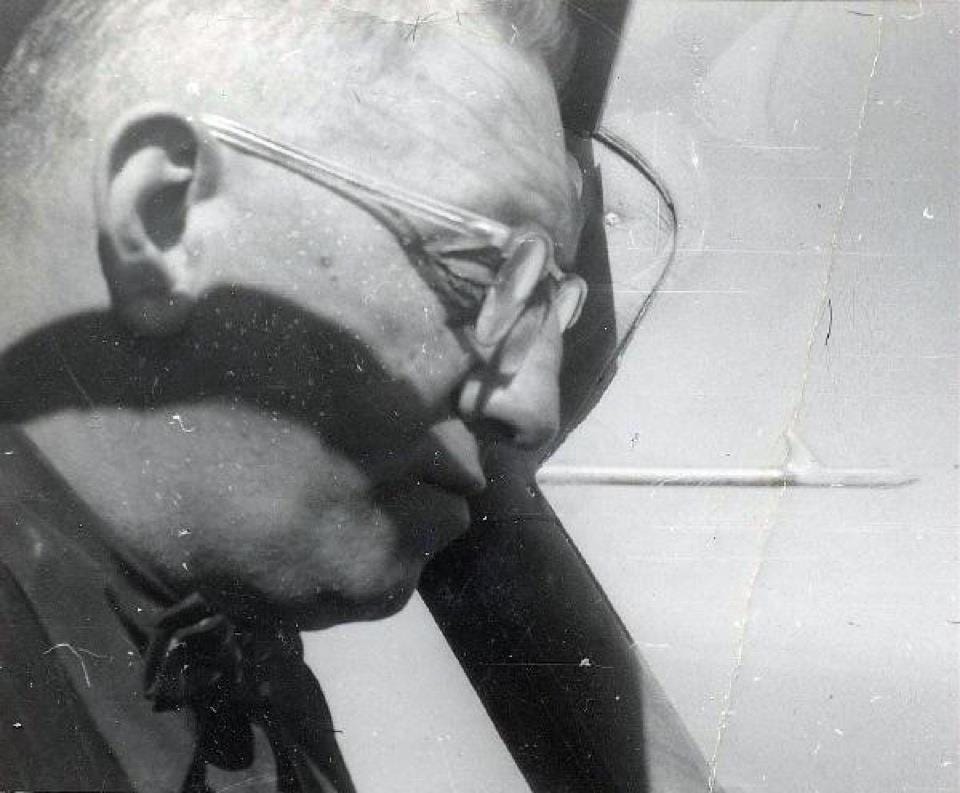

Whichever direction that was, he left an odd legacy. At his funeral, there were multiple bursts of laughter as well as surges of grief. We all expected that he would go before Mom, as she was decades younger, but he came from tougher stock. He was a compulsive storyteller, singing impromptu railroad songs, reciting popular ballads like “The Face Upon the Barroom Floor” and “Curfew Must Not Ring Tonight,” and he told off-color jokes with sexual innuendos. He had earned his pilot’s license (as his younger sister, our Aunt Verby, famously did under the GI bill after WWII). He flew a twin-engine Cessna to construction projects in the region, and claimed to have survived five “forced landings,” extolling with religious reverence that a true pilot never uses the word “crash.” More than once, he daringly buzzed our childhood home in Pittsburgh, swooping down like a hawk, his plane rocking back and forth, tipping his wings like a cocky angel, then soaring off up into the clouds.

He died shortly before his 97th birthday. Though he had a stout heart, his teeth, eyesight, and hearing were faint memories by his nineties. Dementia was settling in. The body has its limits. His death crushed Russell, his devoted caregiver for more than a decade— Dad’s best friend and loyal co-pilot to the end. Within days of the funeral, Russ had another relapse, and once again landed in Western Psych. He didn’t work much after that, retiring on disability by age 40 and passing in 2018 at 56.

At Dad's wake, his brother Clark (who was over 80 himself) privately shared a remarkable story. He recounted how Dad once flew to a golf outing, piloting his airplane. On the course, Dad crossed paths with a group of fellow businessmen who shared his passion for flying and golf. These wheeler-dealers were known for high-stakes wagering, and one of them lightheartedly offered to flip a quarter for Dad's plane. To everyone’s astonishment, Dad accepted the wager and ended up flying the other golfer’s plane home. That story hit me like a pitching wedge. How could anyone casually risk what was a year's salary for many, on the flip of a single coin simply for entertainment? Whether it was at the horse races or playing the lottery, he liked to bet on the long shots. I loved that about him.

I thought: This is what people do when they have money. This is white privilege, no?

Although he lived much of his adulthood in white male privilege, my experience was different. During college at UW Madison, a thousand miles away from home, my own mental health and financial struggles often left me scraping for bare essentials. There were days when a proper meal was out of reach, and I found myself relying on humble alternatives. I kept that a secret. Sometimes a 2-ounce bag of potato chips with a packet of Heinz Ketchup became my makeshift dinner. In college, I learned what it was like to go without, to want.

Dad knew what going without was like. Born in 1904, he was raised in rural Pennsylvania. He became a colorful old-school general contractor and was already a divorced man (with two estranged children) and thirty years older than Mom when they met. She became his secretary, and he gloriously buried himself in work. I can still see his oversized desk at home piled with stacks and stacks of papers.

As the eldest, he was a natural leader despite only having completed eighth grade. During WWI, higher education wasn’t always practical. Children had to help—for survival. His youngest sister Katie (who’s alive and well at the age of 100 as I write this) told us that Dad was born with a veil —the thin membrane or caul covering an infant’s face at birth and a sign predicting the child would do great things. In other cultures, a veil was an ill omen, the child destined to bring misfortune.

From hardscrabble beginnings, he and his brother, along with their jack-of-all-trades-father, founded Moyer Brothers Construction in the 1920s. By the 1950s, there were 1,500 workers on their payroll. They built schools, hospitals, gas stations, and notably most of the toll booths across the Pennsylvania Turnpike by 1941. Dad did well during the Depression and the war years. A real American success story. He knew what wealth felt like.

By the time I was born, the once-thriving business had evaporated, leaving a trail of legal and financial woes, foreign intrigue, shattered dreams, and my already fragile mother frantic. Dad was essentially broke and owed the IRS tens of thousands for the rest of his life. All I had left were his stories and a few dozen eight-by-tens documenting his past success, and in disarray on my bedroom floor like so much lost history. I had no idea as a kid.

You would have liked him if you had met him. Most people did.

Internet technology has been a boon for historical research. While newspaper articles about Moyer Brothers were easy to find, it was the smaller articles that offered a window into Dad.

Starting in 1929, he was arrested for transporting liquor (one bottle of whiskey) and driving while intoxicated during Prohibition. He was acquitted that October, just before the cataclysmic stock market collapse. In 1934 there was a car accident and another drunk driving charge. Acquitted.

In 1940, his firstborn son somehow opened the passenger door, fell out of Dad’s car, and was run over by the car traveling behind them. (No seat belts or child safety locks then.) To add true insult to injury, the boy was pinned under the other car, surviving with a broken leg.

Dad must have been devastated after that, but he soldiered on. In 1944 there was another car crash. He was hospitalized with a broken leg as if by karma. In 1951, the newspaper reported his driver's license was suspended. In 1957 fire trucks were called to his Altoona home. He refused treatment for smoke inhalation. That article referred to his unnamed “wife” waking him while a cigarette smoldered in an overstuffed chair. The “wife” was likely Mom, but there is no record of them ever having been legally married —theirs was likely a common-law marriage. I had no idea. My sister was born soon afterward.

One night in 1967, I have vague memories of him colliding with a motorcycle cop as his Thunderbird bounced off the walls of a Pittsburgh tunnel, careening off the walls of the Liberty Tubes and into the city. The officer’s motorcycle reportedly soared a hundred feet in the air. Thankfully, the man survived with “a concussion, head cuts, and knee injuries.” Dad was acquitted on a technicality— breathalyzer tests did not exist. He loved lawyers but I didn’t get why —until my research. Some stories weren’t in the papers.

Beyond daring flights and bold wagers, there was a darker tale that he hadn’t shared with anyone but me. On a farm way back in the nineteen-teens, there were few amusements, not even radio. But there were cats and dogs for playmates. There was also a generator, likely powered by kerosene. Dad described a Saint Bernard he and a friend hooked up to the machine and laughed at how electricity made their dog dance. Schadenfreude. My heart sank at their crude experiment on a living creature. As kids, we are more capable of stupidity. I know I was.

We all have flaws. Blind spots. None of us is perfect. While Dad had a folksy charm, certain things he did tipped off a darker streak — one was using people to serve his own interests. I was disheartened to witness how adept he was at cleverly masking manipulation as a favor. Secretaries and waitresses were often treated politely as expendable. He’d scrawl illegible hieroglyphics in pencil on his yellow legal pad and have me type them. He’d praise me then quickly take my efforts for granted. I loved him, nonetheless. He was a warm and generous man. He was my Dad, wasn’t he? I believed so, then.

Russell’s untimely death in 2018 led me to take a consumer DNA test. I was intrigued by the fascinating history DNA could reveal through genetic genealogy. The results told another story, one that Dad and Mom had taken to their graves. He was not my biological father.

I was neither shocked nor devastated, two feelings a non-parental event (NPE) typically evokes. I felt mildly bewildered, and intrigued —it was as if a deeply hidden burden had been lifted, a weight I had been unknowingly carrying my whole life. Years before in therapy, I had been unconsciously wrestling with Dad’s shadow side, recalling how he treated me similarly to my mother, contradicting his façade of down-home trustworthiness. He was supportive until he wasn’t, especially with my mother, an adoptee who craved security and his more powerful bodily autonomy that most males take for granted. I always wondered why I never saw him pick up a hammer or a saw in my life. He was a numbers guy. I was not.

I took no pleasure in figuring out the truth and held no ill will toward him, but his behavior left me with lingering questions. Nonetheless, he was like granite in the face of adversity, tough and hard to crack. Perhaps he was more like marble—variegated. Strong and resistant to damage, but porous and more easily stained.

Unlike my siblings, I was skeptical long before the DNA test and tended to align with my mother’s point of view. Observing his calculated self-interest, I had grown more aware of how relationships could be fragile, vulnerable. He struck me as a quintessentially American capitalist, reminiscent of historical figures like P.T. Barnum and his favorite president, Grover Cleveland. Men who felt empowered. Dad was part of a much larger story. He had a kind of unapologetic bravado.

He never mentioned being physically disciplined as a child. His mother had another approach. She taught him the value of reflection by assigning a passage from the family Bible. A small lead weight, a biblical marker, would silently point to a specific passage to contemplate.

The marker gently invited him to seek understanding through mindful reflection, signifying a pause, a moment to focus on a particular piece of wisdom. By engaging with The Word, he was to examine his behavior and seek divine inspiration as Christians had done for centuries.

Dad avoided using physical punishment with us, and I’m glad he did. In my childhood, we had no sacred texts. I wasn’t much of a reader. Mom, as an adoptee, had abandoned Catholicism before my birth, and Dad hadn’t opened a Bible since childhood. Mom had given up reading to me by the time I was five. She had no qualms about ineffectively using physical discipline, justifying its use as if it were self-defense.

The laissez-faire discipline in Dad’s family left an indelible mark on him. Exploring his upbringing helped to shed light on his basic values —his mother’s wholesome influence, and the power of words to shape his worldview. Though he believed in the Almighty, he never attended church in my lifetime. His church was the construction business, and he was wedded to his work more than any person I ever met. He never retired.

I respected him most one day in his seventies as he sat on the edge of his bed in his underwear, shoulders drooping, his body limp. He ugly cried like a baby after my mother telephoned to say she wanted a divorce.

He had a heart after all.

In his late eighties, when he could barely grip a fork and no longer physically work, he struggled with his palsied hand to scribble out litigious ways to recoup money lost to the IRS or get back to work —plying the tools of his trade and legible only to the Almighty: a yellow legal pad and a sharp number two pencil. I have dreams about him every so often. He would have made an incredible writer.

Beautiful, rich, and fascinating insights into your father's life. Thanks for sharing your story with us.

Relationships can be complicated, can't they?! Thank you for sharing a bit of your Dad's life, J.E.